“Do we renovate? Of course we renovate,” Ms. Fisher said. “But what if it happens again, next year and the year after?” – NY Times, 11/23/2012.

Unpleasant Weather: Mother Nature gave us a good smacking in 2012, as if to say “Smarten up! Get your act together!” Here in B.C., outrageous spring rainfall brought terrible mud-slides. All summer in the U.S. and Central Canada, there were devastating droughts. Windstorms knocked out power for millions of people during record heat waves.

When Hurricane Sandy came around, the Onion, a satirical newspaper, published an article headlined, “Nation suddenly realizes this is just going to be a thing that happens from now on.” FEMA appealed for extra flood-relief funds from Congress, President Obama called for insurance companies to do their part, and clean-up efforts began.

If we really accept that “this is just going to be a thing that happens,” now is a good time to revisit our development planning. We really don’t have to live like this. Change is daunting, but doable.

.

Non-Disasters: If you can predict and prepare for a weather event, is it really a disaster? Here in the Okanagan, a frightful cold descends each November, bringing icy roads, traffic accidents and burst pipes. We cope by changing to snow tires in October, turning off the water to outside spigots, and getting our heating systems serviced.

This basic logic – of predictably terrible weather – caused the Australian government to re-think its drought policy in 1992. Essentially, they reasoned: “Long dry spells occur regularly, and are unavoidable. We should be in the business of reducing risks – and social, economic and environmental impacts – not treating each drought as an unforeseen calamity.”

Australia reclassified most droughts as non-disasters, starting down the long road of restructuring their farming sector and water systems. They’ve sucked up a lot of discomfort, but in the end, their society is stronger. Here in North America, we are a decade or two behind – responding to crises.

Not Waiting for Noah: Sandy has been called the perfect storm – a dramatic combination of warm air and hurricane winds hitting a cold air mass – but the damage was made more intense because many people are simply living in harm’s way. Whether for love or money, we’ve built expensive homes along the coastline, laying them right across the railway tracks of the hurricane train. One home in Biloxi, Mississippi, valued at $183,000, flooded 15 times over ten years, costing the federal flood insurance program $1.47 million to rebuild and rebuild.

Meanwhile, the stakes are getting higher: more people in the path of bigger, more frequent, storms. Mark Twain said, “Everybody talks about the weather, but nobody ever does anything about it.” Just as in Australia, economics may be a lever for change.

I heard a lecture recently by a U.S. insurance expert who compared Florida’s liability to a small Caribbean country whose claims can’t be supported by their premiums. The rest of the U.S. pays extra to rebuild Florida, but the costs are escalating. As a result, the insurance industry may force changes that governments are unwilling to make.

Over in the state of North Carolina, legislators recently forbade the use of climate science to establish coastal flood zones for planned developments. However, if you buy there, you might not get a coverage for your beautiful new home by the water. Unlike the federal government, insurers can stop issuing policies after repeated floods, and quit paying to rebuild.

Love is Blind: As long as places are fun (like Manhattan) and beautiful (like Florida), some people will always come back, but hopefully with different expectations. The biggest problem is our not understanding there is a problem, and we are slowly learning.

My step-daughter Lucinda was in New York for Hurricane Sandy. “Actually, it was pretty boring. We had electricity, so we watched videos and ordered out for pizza for four days. There were long lines at all the delis and coffee places.” None of her friends did any preparation except to make extra runs to the liquor store, and in the end considered themselves lucky.

Last June, I had a conversation about climate change with a Bangladeshi shoe-shine man in the Toronto airport. He was putting two sons through engineering school. “Do you think there will be many people moving from Bangladesh because of the sea-level rise?” I asked. “Oh no,” he smiled, “It is so beautiful along the coast of my country, people will move out of the way of the water, then they will always move back.”

I shrugged my shoulders. If they are okay with regular flooding, who am I to say differently? It’s a form of adaptation.

Unnatural Disasters and Being Brave in a New World: I am given hope, with the mountain of challenges for climate adaptation, remembering that each generation has had vast challenges of their own.

During the Cuban Missile Crisis, my father was teaching high school in Los Angeles. The floor-to-ceiling windows of his classroom looked out over downtown L.A. – which was (naturally) considered a target in the upcoming nuclear holocaust.

The administrator came in to share the emergency response plan: “Tell the students to get under their desks, and keep them inside until their parents come. If a fire starts, put it out.” He handed my dad a first aid kit, and walked out of the room. It’s a funny story when my dad tells it – grinning with irony.

So, despite complexity of planning in this changing environment with a growing global population, I feel much more empowered than my father did. Our landscapes and resource use will likely change radically during in my lifetime, but we can respond, plan, prepare, and adapt. That’s the nature of humanity. I get impatient, but I think we’re finding our way forward – bravely, into this new world.

So, despite complexity of planning in this changing environment with a growing global population, I feel much more empowered than my father did. Our landscapes and resource use will likely change radically during in my lifetime, but we can respond, plan, prepare, and adapt. That’s the nature of humanity. I get impatient, but I think we’re finding our way forward – bravely, into this new world.

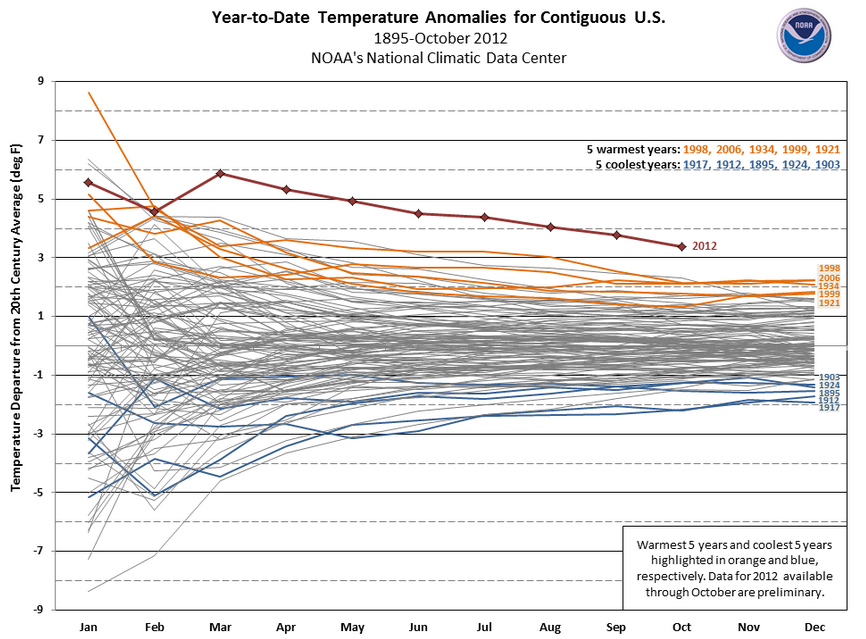

And One More Thing: After publishing this post, I found an outrageous 2012 temperature chart on Peter Gleik’s Twitter feed (in case anyone has any doubts about the weirdness of the weather). I haven’t been able to find anything comparable for Canada, but this has to be worth a thousand words.

Witty, informative and thought provoking as always. People adapt to real and perceived crises in different ways. Get a group of people together to plan for a future risk – now that’s what I call an interesting meeting.

Thank you, Kathy! There was a great piece in the New York Times yesterday about all of this, and to me it definitely moves in the Australian direction of social restructuring. I really feel for the lower and middle class communities who are facing huge premium increases after Hurricane Sandy, but we are up against the mighty forces of nature, and there’s no holding back the storm surge. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/29/nyregion/cost-of-coastal-living-to-climb-under-new-flood-rules.html?ref=nyregion

In several posts of late from different sources and on different topics, I continually see trends of predictable consequences or some mention of awareness of future consequences for a variety of difference scenarios (e.g., see http://thetyee.ca/News/2012/12/12/BC-Treaty-Troubles/ for predictions from early First Nations treaty negotiations). Ironically, it seems, we still continue to make the same choices in light of this wealth of information. This begs the question, is humanity adaptable enough to make positive changes going forward, or will we continue to make the same choices over and over again, irregardless of the consequence? If we cant adapt quickly and begin to learn from historic mistakes, I do truly fear for future generations. In my opinion, the consequences of poor or ill made choices are becoming far greater with each passing year because population growth is expodential, meaning the econmic and social conseqeunces must be greater as time goes on.

Thanks Anna, very insightful.

Hi Jason,

Thanks for your comments. I’ve also been following an adaptation discussion group on LinkedIn, and there is a lot of discussion about how much do we need to know about the consequences of climate change (for example – how high sea level will rise) before we make plans. It’s the two different aspects of the precautionary principle. Do we wait until we are sure about something, to avoid unintended consequences, or do we go ahead with the best available knowledge, as a precaution against the disaster of doing nothing?

Anna