“Live in the questions, and gradually, and almost without noticing, you will enter the answers and live them also.” – Rainer Maria Rilke

What does water sustainability look like? How will we know when we get there?

With climate now a moving target, sustainability – as a concept – may lend a false sense of future security.

With climate now a moving target, sustainability – as a concept – may lend a false sense of future security.

These green pastures probably aren’t a place we actually arrive – a utopia of living roofs, light rail, and urban agriculture. Instead, I’ve been trying to think of sustainability as adapting to whatever change happens – while protecting the systems of our little planet for those who come later.

“Resilience” captures the same idea – the capacity to rebound and rebuild after a forest fire, or like our immune systems, to keep us healthy in a world of germs.

For water management – like everything – to reach a state of readiness, we need to start with what we know, pursue the “known unknowns,” and (hopefully) reveal the unknowns we’ve never considered.

In this spirit, over the past six years, a group of agencies and researchers has undertaken a water supply and demand assessment of the Okanagan: looking for practical paths forward, so that decisions can be based on science, information gaps are uncovered, and we get a better idea of what to expect from climate change.

In this spirit, over the past six years, a group of agencies and researchers has undertaken a water supply and demand assessment of the Okanagan: looking for practical paths forward, so that decisions can be based on science, information gaps are uncovered, and we get a better idea of what to expect from climate change.

There is a lot of history. The Okanagan has had water shortages since irrigated agriculture arrived more than 100 years ago. In the past, we’ve taken a supply-side approach, building dams and diversions and drainage ditches. But if anything, the balancing act has become more difficult.

The challenge is the inexorability of change. More people come in, more fields are planted, and we start to recognize that fish want water too. Town councils ask, “Is there a real concern? Are we going to run out of water?”

And – despite B.C.’s fame for timber and rain – the rest of the province has similar water problems. Some relate to cost (dams are expensive), some to quality (saline groundwater), and some to storage capacity (where will we put the next reservoir?). Everywhere, we need to know more about climate change. As my dad says, “Nature is a tough mother.”

In the early 2000’s, B.C. was gearing up to overhaul the century-old Water Act, and needed a better way to make water decisions. Eyes turned to the Okanagan as an extreme case: Canada’s only desert, with endangered species, drought, fires, rapid population growth, and inevitable conflict. It’s a relatively small area, with all the problems anyone would want to study – and has baseline numbers from 1974 for comparison.

To plan for future development, environmental protection and water security, we need to know how much water is coming in, and how much is taken out – and where. The resulting Okanagan water supply and demand assessment has been an adventure in science and technology – and in learning how to collaborate on a difficult, long-term project.

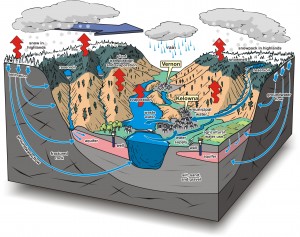

Supply, by itself, is very complex – taking in snowpack, surface and groundwater flowing slowly south in streams and aquifers, along with the return flows from wastewater and over-irrigation. The geology matters too – where the water soaks in, or runs off.

On the other side of the equation, water demand ranges from evaporation, as the demands of dry air suck water off the surface of lakes, to evapotranspiration – pumping water through plants on grassy slopes and forested mountains; water for healthy fish and stream systems; water for farmers; and water for kids brushing their teeth with the tap running.

Many of the models had to be created from scratch. For climate, researchers scaled down global models to half-kilometre grid squares, laid across the valley topography. In each square, they can project weather patterns into the future. This was applied to an intensely-detailed water demand model, estimating the water needs of every piece of land – given vegetation, crop, and water source. Even just getting to the details of how water collects and flows through to the lakes – pushed computations to their limit.

Not everything ran perfectly smoothly, but even that had its uses – finding weak areas and pitfalls, so that other watersheds can do studies faster and more efficiently.

Not everything ran perfectly smoothly, but even that had its uses – finding weak areas and pitfalls, so that other watersheds can do studies faster and more efficiently.

With the help of (what seemed like) all the water people in B.C., the result has become a huge resource of water information – and a much clearer road ahead, with less unknowns. While in previous posts I’ve touched on what we found, we’ve collected everything related to the project on its own website.

Some some of the results are making me think hard:

- Okanagan residents use twice the Canadian average for water

- Most of this difference is from watering outdoor landscaping

- We depend on upland reservoirs for 20% of water supplies

- The biggest drought risk is for summer low-flows in streams

- Okanagan streams are marginal for fish in the best of conditions

- Agricultural irrigation is increasingly efficient, but…

- Longer, hot summers will increase water demand by plants in agriculture, as in nature

- We need agreements in place to reduce conflict over summer stream flow

When we completed the modeling, it felt like the Churchill quote, “This is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.” Now, our work is to apply all this information to real plans – for irrigation, development, storage, and licensing; and for drought-response plans that link community water supplies.

In this case, the Okanagan’s weakness – having among the worst water problems in Canada – has been our strength – provoking a full-on effort to assess what we have, where it comes from and where it goes. The assessment was complicated, but ultimately doable – inspiring other areas in B.C., and giving them models to work with.

In the context of sustainability and resilience, the valley still faces unfolding future drought risks, population growth, and the need for food security and environmental protection. All we have are the tools at hand – but we now have more of them, and they have been tested and sharpened.

To me, the process has also been a galvanizing force for water scientists in Canada: we have a huge capacity for collaboration and innovation, people working together with a clear vision of the common good, and, in the end, what will be good for the commons.

The following is some media footage from the “launch” of the results in 2010 – when the modeling portion was completed.

And this film was made to celebrate a Premier’s Innovation award for the Water Demand Model.

Inspiring work. I will be forwarding this link to other colleagues outside the Okanagan. The story is one not only of science but also of collaboration. Kudos to all.

Thank you, Kathy. It was an inspiring project to work on. Great team! Anna

Pingback: Learning from the landscape: cultivating a sense of place in the Okanagan. | | Building BridgesBuilding Bridges

Pingback: Weddings, weird weather, and where to fit everyone - water, population growth and climate changeBuilding Bridges

Pingback: Water Day, every day | | Building BridgesBuilding Bridges