“This is your time and it feels normal to you, but really there is no normal. There’s only change and resistance to it and then more change.“ – Meryl Streep

I’ve been writing about change lately – change in climate and population. But it will take even more change to adapt to new conditions. The challenge is knowing where we are vulnerable and how to respond, so we can protect the things we love. But how do we get through the inertia to action?

Summer rains on Kootenay Lake – photo taken a few days before and a few kilometres north of the Johnson’s Landing slide. Courtesy of Brynne Herbison.

It’s as true for individuals as whole communities. People tend to trust their odds for most things – but suddenly, without warning, the ground can shift beneath us.

I’ve been deeply unsettled by news of the mudslide in Johnson’s Landing last week – a place I’ve visited often. A tragedy is the worst kind of catalyst for change.

After a month with twice the record rainfall, Gar Creek unleashed a debris flow down the mountain. At 10:30 Thursday morning, three houses sat surrounded by meadows and forest. By 11:30, they had been swept away by a wall of dirt, rock and twisted trees.

Four people lost their lives, and all of BC was shaken.

It’s now a high priority to get the geotechnical experts out there. What triggered it? How can we prevent it from happening somewhere else? There are countless creeks in British Columbia.

And what was the role of climate change? It’s almost an academic question in this context. One of the biggest challenges with a shifting climate is that there are no direct links to specific events. There have always been freak floods and catastrophic landslides.

More than anything, tracking climate change is a process of counting anomalies – estimating probabilities, estimating risk. How often has this weather happened in the past? How often is it happening now?

A tragic debris flow through Johnson’s Landing becomes an entry on the ledger of extreme weather disasters, along with the floods last week in Japan and the scorching drought of the corn-belt. More and more, planners have to rely on cumulative statistics to give some direction, to help communities reassess their odds in changing times, and regain stability.

But it is one thing to have a sea of statistical information, and another to know what to do with it.

Coverage on the Insurance Bureau of Canada’s push for climate risk assessments. Click on the picture to watch the video in a new window.

I felt a rush of hope at a recent talk by Robert Tremblay, of the Insurance Bureau of Canada. They have an elegant new approach for assessing the climate risks of flooding storm drains and sewer backups in urban areas.

It sounds mundane, but has a huge impact. Only yesterday they had to evacuate a medical clinic in Nelson after a heavy rain backed up the pipes.

This new method won’t help rural communities like Johnson’s Landing, but it can save other homes for other families.

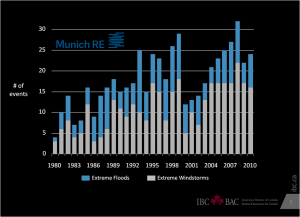

Data from a global reinsurance company, Munich Re, showing the increase of extreme weather events. Click on the picture to make it bigger. Image courtesy of Robert Tremblay of the Insurance Bureau of Canada

For decades, insurance companies have been collecting information about floods, fire and wind, and where the damages are. They see the effects of climate change very clearly – globally, extreme floods tripled between 1980 and 2010. Wind events doubled.

Now they are making GIS output from their risk assessment tool freely available to urban planners – pushing to get these kind of analyses into the mainstream, and trying to stem the rising tide of damage from failing infrastructure. It’s their homes and businesses, too.

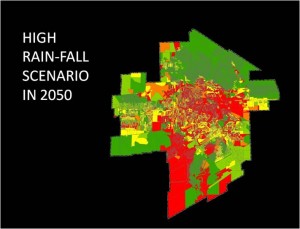

Instead of rough estimates, planners can use the municipal risk assessment tool to map where the worst infrastructure failures have happened in the past, and overlay climate projections for increased intensity, duration, and frequency of rainfall. They can show – ahead of time – where the risks are.

This is an example of a risk map from the Insurance Bureau of Canada’s municipal risk assessment tool. Image courtesy of Robert Tremblay of the IBC.

It’s a simple and powerful approach, with implications that reach far beyond flooded basements in urban areas. In the future it can be expanded to look at many more weather impacts.

But most importantly, I think it can help us make sense of climate change at the level of the basic social fabric – our homes and neighbourhoods – and for the first time, make it a normal part of planning.

This tool is a huge important step forward if we want to move beyond the extremes of inertia and disaster-driven policy response.

Of course there will always be catastrophes. I grieve for the Johnson’s Landing community, and for everything that has been lost.

Likely the slide was a combination of terrible circumstances, and the heavy rain contributed only a part – but if we can have a standard process for understanding climate risks in cities, I have hope for rural areas, too.

It’s not so much that we lack ways to expose where we are vulnerable, we just haven’t brought them into common practice.

I can accept that we will have more extreme weather, but I want to see progress in how we respond and adapt. I want to know the risks.

The following is a video clip about the mudslide, courtesy of Shaw Media.

Here’s an interesting follow-up, that just came out in the Vancouver Sun:

“Climate change could bring about more natural disasters”

Pretty powerful stuff. I have not visited Johnson’s Landing, but having recently come back from Nepal, where I saw villages and terraces with the scars of landslides scattered around, I can appreciate how a tragedy like this can tear at our heart strings.

These things leave me with many questions and few easy answers. How do we live with this uncertainty? How do we make ourselves and our communities more resilient in the face of this uncertainty? What is the right balance between personal accountability and collective support? How can we build systems that are more resilient when doing so comes into conflict with other cherished values of privacy, autonomy, property rights, etc.?

Hi John, Those are big questions! These kind of disasters are outside of my experience, but I do know that small changes in how we do business can have a big effect, or just looking at the information differently (for example, as the insurance data allows). As I discuss in the post, we need a better approach to risk assessment and prediction.

I hope in many cases we will be able to take care of the worst hazards with some basic changes in forestry or water system practices, a change in the way we monitor (could be with trained community members), and perhaps additions to the emergency response systems. For the question of landslides, there are much more qualified people out there who may be able to respond better.

Glad to have you back in the country, Anna

My last encounter with mudslides in a place I was familiar with was Seattle in the 1990s. There is a steep slope near the cemetery on Capitol Hill with a beautiful view of the Cascades. In the 1930s, it slid and destroyed all the houses on it and killed the residents. But the view was so spectacular, that others rebuilt houses on the same spot. One of the new houses was geotechnically engineered to withstand mudslides. It survived when the hill slid again in the 90s, and the other ones did not. I drew a lesson from that about engineering houses on steep slopes. This lesson is completely useless in terms of the Johnson’s Landing situation.

We go through life figuring out what is safe and what is not, and how to keep ourselves safe, and what other people are doing wrong.

And then we find out that all of our accumulated wisdom is insufficient to face the actual dangers.

So we either have to become very paranoid or very brave.

Hi Julian,

I think living a full life requires bravery, regardless. But I think I’m more optimistic than you. Despite the feeling of random catastrophe about this slide, I do think there are ways to avert many of the impacts from climate change – and most of them we already know how to do.

Anna

Pingback: The Value of Water | | Building BridgesBuilding Bridges

Pingback: Lessons from Sandy: disaster isn’t our only option | | Building BridgesBuilding Bridges

Climate change related disasters are real threat to international community. India faces many kinds of threats of disasters like floods, land slides, cloud burst, droughts, fog, coastal erosion and sea level rise impacting the lives of millions of poor and ordinary people. The most important dimension to cope with such disasters is making people aware,alert and partners in the process of adaptability. It needs a process of education and sharing to minimize losses. The way forward is to be knowledgeable to use local resources,experience and expertise to minimize impact.

I agree completely with you Colonel. The government can’t know the landscape as well as the locals, and we need to get information to the people so they understand the risks, and how to prevent them.

Thank you for your comment!

Anna

Pingback: On not waiting for Noah | Building Bridges