“When it is obvious that the goals cannot be reached, don’t adjust the goals, adjust the action steps.” – Confucius

It is hard to think of anything more controversial than “Americans taking our water.” Questions come up at almost every public meeting. The concerns are not entirely unfounded: in general (as Trudeau famously remarked), living next door to the US is a lot like sleeping next to an elephant – feeling every twitch and grunt. This underlying sentiment, and the need to meet Okanagan water demand and environmental flows while being good neighbours, has created intense interest in the renewal of the International Joint Commission’s (IJC) agreement for Osoyoos Lake.

In this post, I want to share our “Made in the Okanagan” solution for the 2013 renewal of the Osoyoos Lake Operating Orders for Zosel Dam.

The orders’ main goals are to control floods and prevent water shortages. But everyone wants more certainty about water supplies on both sides of the international border – including water for the Okanagan’s reviving sockeye run. The reach most at issue for the US is the short stretch of river between the dam and its confluence with the mighty Similkameen River. While “certainty” may be out of reach in this era of environmental change, I feel we’ve come up with a strong set of action steps to get to our (bilateral) goals.

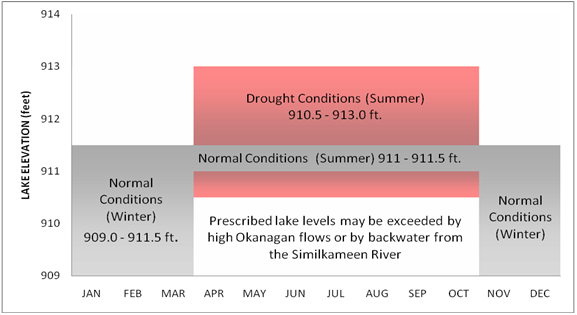

The last time I posted about this, we’d just been at the Osoyoos Lake Water Science Forum, vigorously discussing the technical studies guiding the orders’ renewal. Currently, lake levels are set at a fixed range, adjusted at specific dates in spring and fall. This arrangement has not worked well for residents – too much flooding and erosion – or for fish, with low water conditions during the seasonal transition. If droughts are declared, because of one of three different factors (low flows in the Similkameen, in Okanagan Lake, or low precipitation), extra water is held in Osoyoos lake as a storage reservoir – exacerbating problems as boat wakes and windy weather push waves up onto beaches and threaten properties.

Other issues come in. The Okanagan has intensely variable flows, and current orders don’t reflect or respond well to environmental conditions. One of the studies, done by American researchers, recommended guaranteeing flows out of Zosel Dam; obviously controversial on this side. Also, because few fish studies have been done, there is a lot of uncertainty about what the environmental flow should be. A Canadian study recommended that lake operations need to be more flexible to respond to climate change over time.

Since the studies were done by independent teams, it wasn’t obvious – taking all the reports together – what the ‘solution’ should be. The Okanagan Basin Water Board wanted to do its own analysis, and provide the IJC with a set of recommendations that would resolve problems on both sides of the border, while meeting Okanagan water needs.

In this Google Map, you can see that the US Okanogan river has just a short stretch between Zosel Dam, south of Osoyoos Lake, and the confluence with the much larger Similkameen River.

The authors of our Okanagan report are Canadian scientists and engineers (Brian Guy; Don Dobson; and Jim Mattison) who worked on five of the eight IJC studies. In the end, they found straightforward answers.

The Boundary Waters Treaty doesn’t allow the IJC to govern flows into Osoyoos Lake (calling water from higher up the lake system), so it can’t guarantee flows out of Osoyoos Lake without infringing on Canadian sovereignty. Most of the problems with flooding and seasonal low water conditions below the dam can be solved with more flexible dam operations.

Giving a bit more discretion to the dam operators, and automating the gates would remove the need to declare drought years – and the often unnecessary holding of high waters behind the dam.

Historically, we’ve managed to meet fish flows below the dam through cooperative agreements – these are not as binding or cumbersome as an international treaty agreement, but have the advantage of flexibility. We can easily update cooperative agreements as we learn more about what fish need at different times of the year, or in response to climate change bringing higher or lower flows. If climate change greatly increases water demands for fish and human needs below the dam, it would be possible to develop a side channel, bringing in Similkameen water above the natural confluence.

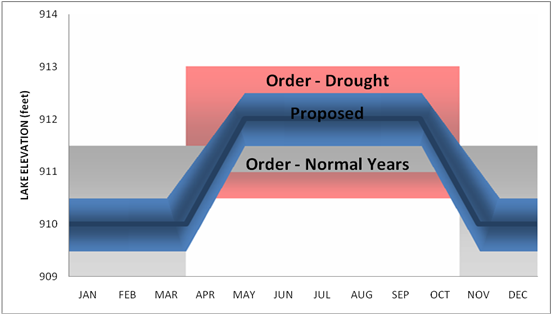

This diagram shows the new, more flexible, proposal for Osoyoos lake levels, superimposed over the existing orders.

In the end, the proposed new orders in the Osoyoos Lake Operating Orders Recommendations Report “tune up” and modernize the existing orders, but aren’t sweeping controversial changes. Their relative simplicity is a strength, because they resolve problems for residents, but make an easier set of choices for dam operators.

If only we could find a sweet spot like this for all our other watershed issues.

I thought I’d close with a quote from the cooperative agreement of 1982, because this is what it is all about: “both governments recognize that the sharing of international waters also imposes the responsibility of mutual trust, harmony, and understanding. It is in this spirit of friendship and cooperation that this plan has been developed.”

Pingback: No vacation in the Salmon Nation | Building Bridges

Pingback: Building Bridges for Okanagan Water in 2012 | Building Bridges

Pingback: Why I stopped worrying and learned to love Water Act Modernization | Building Bridges

Pingback: Osoyoos Lake – bringing international agreements down home | Building Bridges